Introduction

In this blog post, we dive deep into tokenization, the very first step in preparing data for training large language models (LLMs).

Tokenization is more than just splitting sentences into words—it’s about transforming raw text into a structured format that neural networks can process. We’ll build a tokenizer, encoder, and decoder from scratch in Python, and walk through handling unknown tokens and special context markers.

By the end, you’ll not only understand how tokenization works but also have working Python code you can adapt for your own projects.

The Three Steps of Tokenization

At its core, tokenization involves three main steps:

- Splitting text into tokens (words, subwords, punctuation).

- Mapping tokens to token IDs (unique integers).

- Encoding token IDs into embeddings (vector representations).

In this post, we’ll focus on steps 1 and 2.

Preparing the Dataset

For demonstration, we’ll use The Verdict by Edith Wharton (1908), a short story available for free.

https://github.com/rasbt/LLMs-from-scratch/blob/main/ch02/01_main-chapter-code/the-verdict.txt

import re

# Load dataset

with open("verdict.txt", "r") as f:

raw_text = f.read()

print("Total characters:", len(raw_text))

print("First 100 chars:", raw_text[:100])

Output:

Total characters: 20479

First 100 chars: I had always thought Jack Gisburn...Step 1: Tokenizing Text

We’ll use Python’s regular expressions (re) to split text into words and punctuation.

text = "Hello, world. Is this-- a test?"

result = re.split(r'([,.:;?_!"()\']|--|\s)', text)

result = [item.strip() for item in result if item.strip()]

print(result)Output:

['Hello', ',', 'world', '.', 'Is', 'this', '--', 'a', 'test', '?']

👉 Notice how punctuation marks (. , !) are separate tokens.

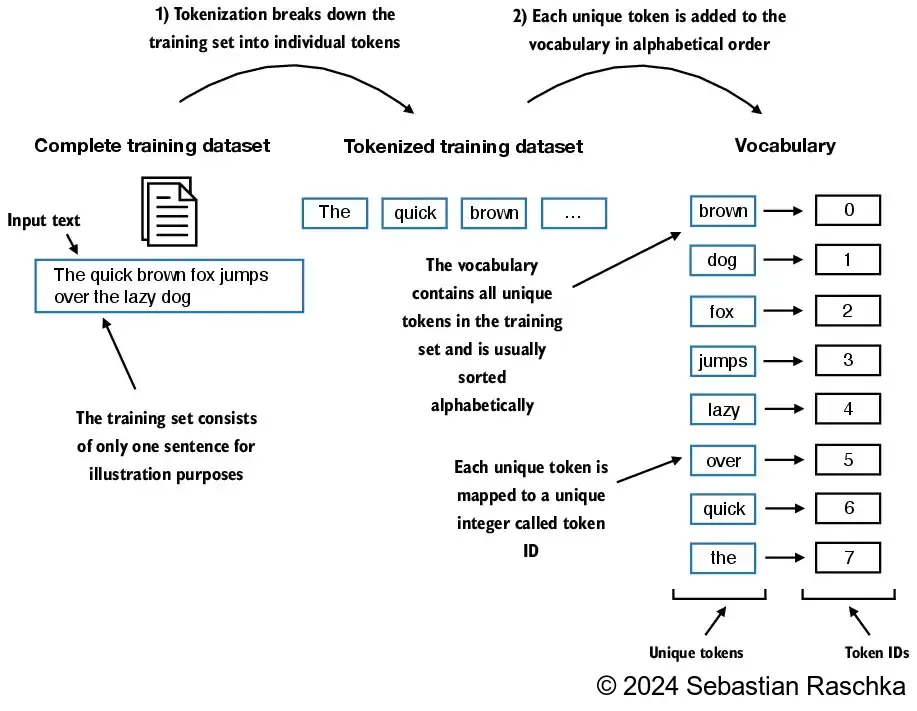

Step 2: Building a Vocabulary and Assigning Token IDs

Now we build a vocabulary: a sorted list of unique tokens mapped to integers.

# Example tokens

tokens = ["the", "quick", "brown", "fox", "jumps", "the"]

# Vocabulary (unique + sorted)

vocab = sorted(set(tokens))

print("Vocabulary:", vocab)

# Map tokens to IDs

token2id = {tok: idx for idx, tok in enumerate(vocab)}

id2token = {idx: tok for tok, idx in token2id.items()}

print("Token → ID:", token2id)

print("ID → Token:", id2token)

Output:

Vocabulary: ['brown', 'fox', 'jumps', 'quick', 'the']

Token → ID: {'brown': 0, 'fox': 1, 'jumps': 2, 'quick': 3, 'the': 4}

Implementing a Tokenizer Class

To make this reusable, let’s implement a Tokenizer class with encode and decode methods.

class SimpleTokenizerV1:

def __init__(self, vocab):

self.str_to_int = vocab

self.int_to_str = {i:s for s,i in vocab.items()}

def encode(self, text):

preprocessed = re.split(r'([,.:;?_!"()\']|--|\s)', text)

preprocessed = [

item.strip() for item in preprocessed if item.strip()

]

ids = [self.str_to_int[s] for s in preprocessed]

return ids

def decode(self, ids):

text = " ".join([self.int_to_str[i] for i in ids])

# Replace spaces before the specified punctuations

text = re.sub(r'\s+([,.?!"()\'])', r'\1', text)

return textExample:

tokenizer = SimpleTokenizerV1(vocab)

text = """"It's the last he painted, you know,"

Mrs. Gisburn said with pardonable pride."""

ids = tokenizer.encode(text)

print(ids)Handling Unknown Tokens and End-of-Text

Real-world text contains words not in the vocabulary. To handle this, we add special tokens:

<UNK>→ for unknown words<EOT>→ for end of text

all_tokens = sorted(list(set(preprocessed)))

all_tokens.extend(["<|endoftext|>", "<|unk|>"])

vocab = {token:integer for integer,token in enumerate(all_tokens)}Updated Tokenizer (V2):

class SimpleTokenizerV2:

def __init__(self, vocab):

self.str_to_int = vocab

self.int_to_str = { i:s for s,i in vocab.items()}

def encode(self, text):

preprocessed = re.split(r'([,.:;?_!"()\']|--|\s)', text)

preprocessed = [item.strip() for item in preprocessed if item.strip()]

preprocessed = [

item if item in self.str_to_int

else "<|unk|>" for item in preprocessed

]

ids = [self.str_to_int[s] for s in preprocessed]

return ids

def decode(self, ids):

text = " ".join([self.int_to_str[i] for i in ids])

# Replace spaces before the specified punctuations

text = re.sub(r'\s+([,.:;?!"()\'])', r'\1', text)

return textNow, unseen words are mapped to <UNK>.

Special Context Tokens in LLMs

Beyond <UNK> and <EOT>, LLMs often use:

<BOS>(Beginning of Sequence) – Marks the start of text.<EOS>(End of Sequence) – Marks the end.<PAD>(Padding) – Ensures equal sequence length in batches.

💡 GPT models (like GPT-3/4) mostly rely only on <EOT> to separate documents.

Why GPT Uses Byte Pair Encoding (BPE)

Our tokenizer treats entire words as tokens. But what if a rare word appears? GPT solves this by breaking words into subwords using Byte Pair Encoding (BPE).

Example:

"chased"→"ch","ase","d"

This way, even unknown words can be represented through known subword pieces. We’ll explore BPE in the next lecture.

Recap

In this post, we learned:

✅ Tokenization = breaking text → tokens → IDs

✅ How to build a vocabulary and assign token IDs

✅ Implementing an encoder/decoder tokenizer class in Python

✅ Handling unknown tokens and using <EOT> for document separation

✅ Why large-scale models prefer subword tokenization (BPE)

Refrences: https://github.com/rasbt/LLMs-from-scratch/tree/main

For a high level view on tokenization read this: https://learncodecamp.net/tokenization/

1 thought on “Tokenization in Large Language Models: A Hands-On Guide”